Notes on "Retrieval Augmented Reinforcement Learning"

“Retrieval Augmented Reinforcement Learning” is a paper that I’ve been meaning to really get into for a while now. As far as I’m aware, it’s currently the only paper that really addresses how to both learn to retrieve and act at the same time. Because there’s a lot of stuff going on in the paper, I found some of the details (particularly the implementation) a bit difficult to parse, so I’ve put together some notes outlining how the various pieces come together.

Motivation

Before we dive into the details, though, let’s discuss what problem we’re trying to solve, and why. Typically in reinforcement learning, we distill the outcomes of thousands of episodes worth of experience into a fixed, parametric model (e.g. a neural network). While this has been shown to work for a large number of problems, there’s an argument that can be made that it’s not the most efficient way we can use experience.

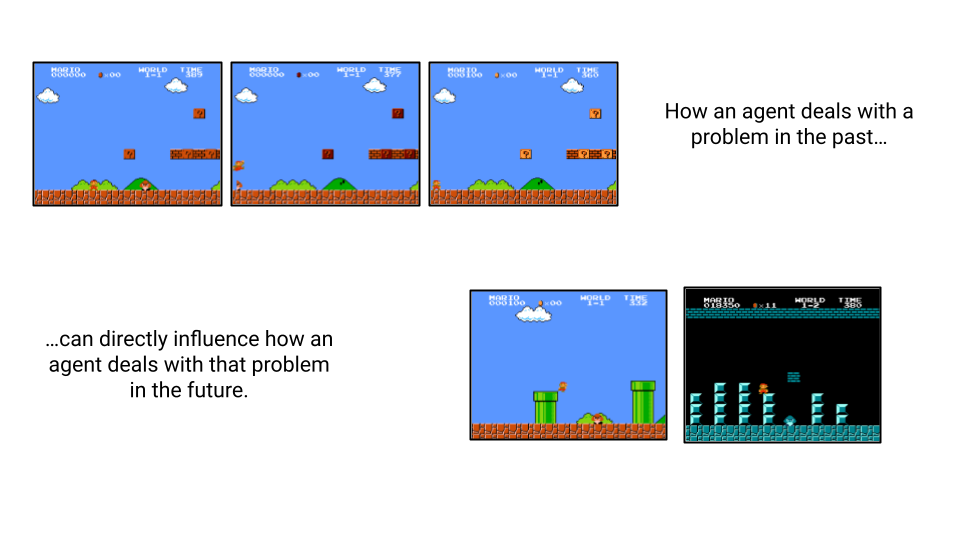

For example, consider the task of learning to play the first level of Super Mario Bros. Aside from the inherent challenges of platforming, the player must also learn how to deal with enemies encountered along the way. On your first brush with a Goomba, you might try running into it and find that you instantly die. Afterwards, you might try to avoid it by jumping around it, but that’s still tricky and can be an error prone strategy. Finally, you might try jumping directly on its head, and find that this gets rid of the Goomba entirely, and nets you some points in the process. Based on that one experience, you now know how to deal with every Goomba you encounter from here on out.

Now imagine how an RL agent would deal with this task. The agent would have to “see” the outcomes of Mario touching a Goomba hundreds of times before it understands that it has to be beaten by jumping on its head, since it has no ability to query past experience, i.e. long term memory. What takes a five year old human less than an hour to master can take well over a day for an RL agent to beat.

Aside from being data inefficient, the traditional RL paradigm is also parameter inefficient. All experience that can influence an agent’s behavior must be distilled into a network’s weights. If solving a task requires understanding how to deal with a large number of unique enemies (as in Super Mario Bros.), all of that information has to be stored in the weights, which can results in really big models.

To combat these inefficiencies, this paper explores an alternative paradigm, where past experience is encoded offline and queried at runtime to improve value estimates of actions. Basically, given a dataset of past experience, the agent can learn during training to retrieve relevant trajectories and act upon them. This is similar to the way we just described how a human beats Super Mario Bros., and the benefit is clear — rather than using experience purely for training the model, you can also use it to inform the model of good actions to take at runtime.

Related Work/Context

Episodic RL

This is not the first time RL researchers have tried using past trajectories to improve a policy’s performance outside of training. The general family of techniques is called episodic RL, named after episodic memory from cognitive psychology. The papers “Model Free Episodic Control” and “Neural Episodic Control” both explore these ideas.

Traditionally, you query previously seen trajectories by their similar to the current state, then use a weighted average of the returns to predict the current return. It’s a bit like model-based tree search, except instead of simulating future trajectories to estimate action returns, you take previously seen trajectories and use their returns to estimate action returns.

A big difference between previous episodic RL approaches and this paper is that the approach outlined here allows the agent itself to determine how retrieved information is used. Rather than directly using the past returns, the agent instead learns to use the information present in retrieved trajectories.

Retrieval Augmented Generation

The paper also cites the recent trend of retrieval augmented generation (RAG) as an inspiration. If you’re reading this post, chances are, you probably already know what RAG is. For completeness, the quick version of it is that a system (usually some kind of chatbot) receives a query, retrieves the most relevant passages for that query, then passes in both the query and retrieved passages to a language model to generate the final answer. Because of that retrieval step, not only does the language model not have to memorize a ton of information, but responses also tend to be more factually accurate.

RAG systems tend to learn to retrieve first (e.g. by training a retrieval model on MS MARCO), then learn to generate responses based on that information. In contrast, this paper learns both how to retrieve and how to act at the same time, which is more difficult, but also more interesting.

The Approach

Let’s construct this system, piece by piece.

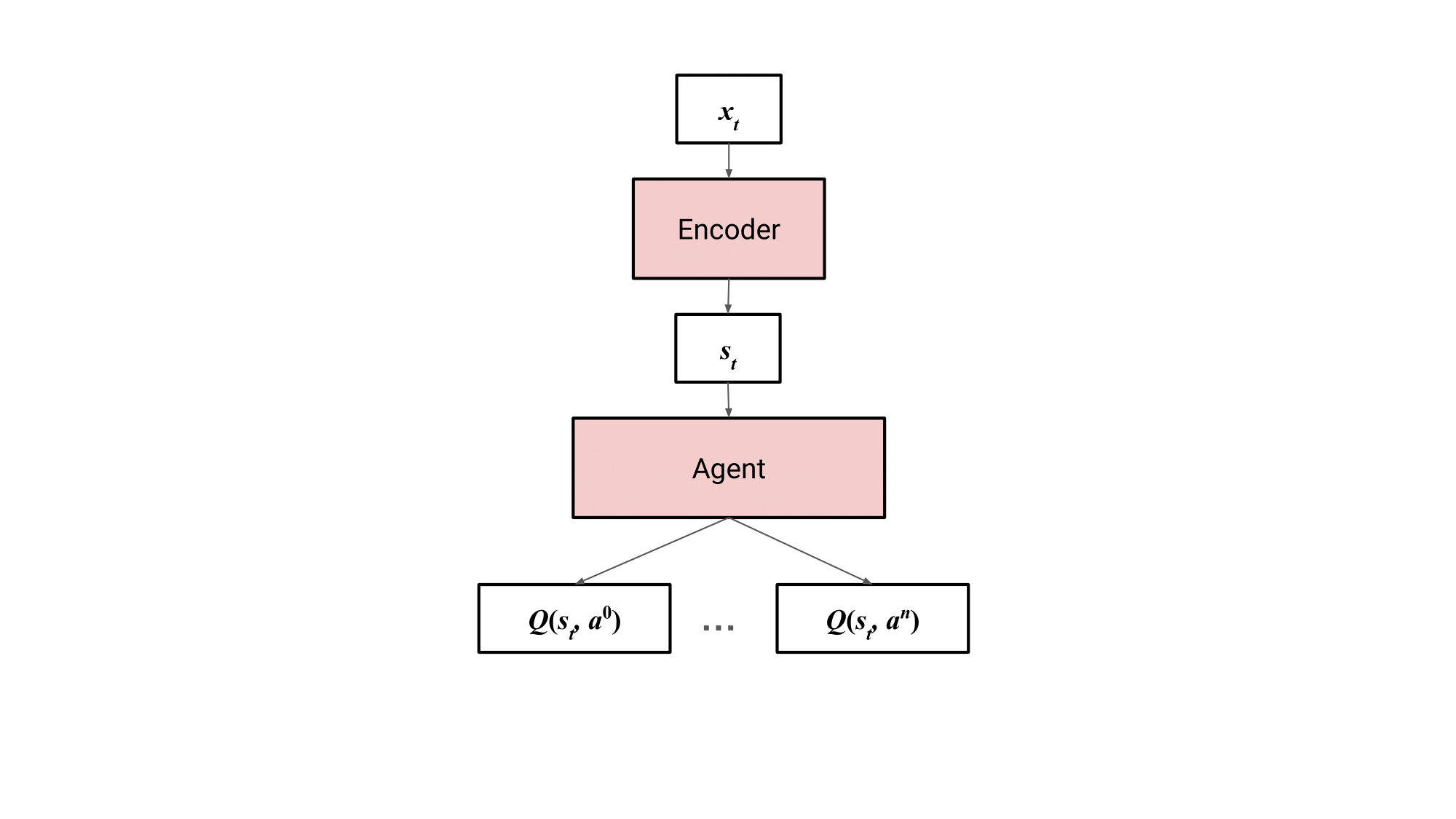

A DQN takes in a state and outputs the expected return for each action, . The paper slightly modifies this and adds an encoder, which converts input/observation into internal state . The encoder can be anything appropriate for processing the input, for instance, a ResNet for images. This setup forms the agent process.

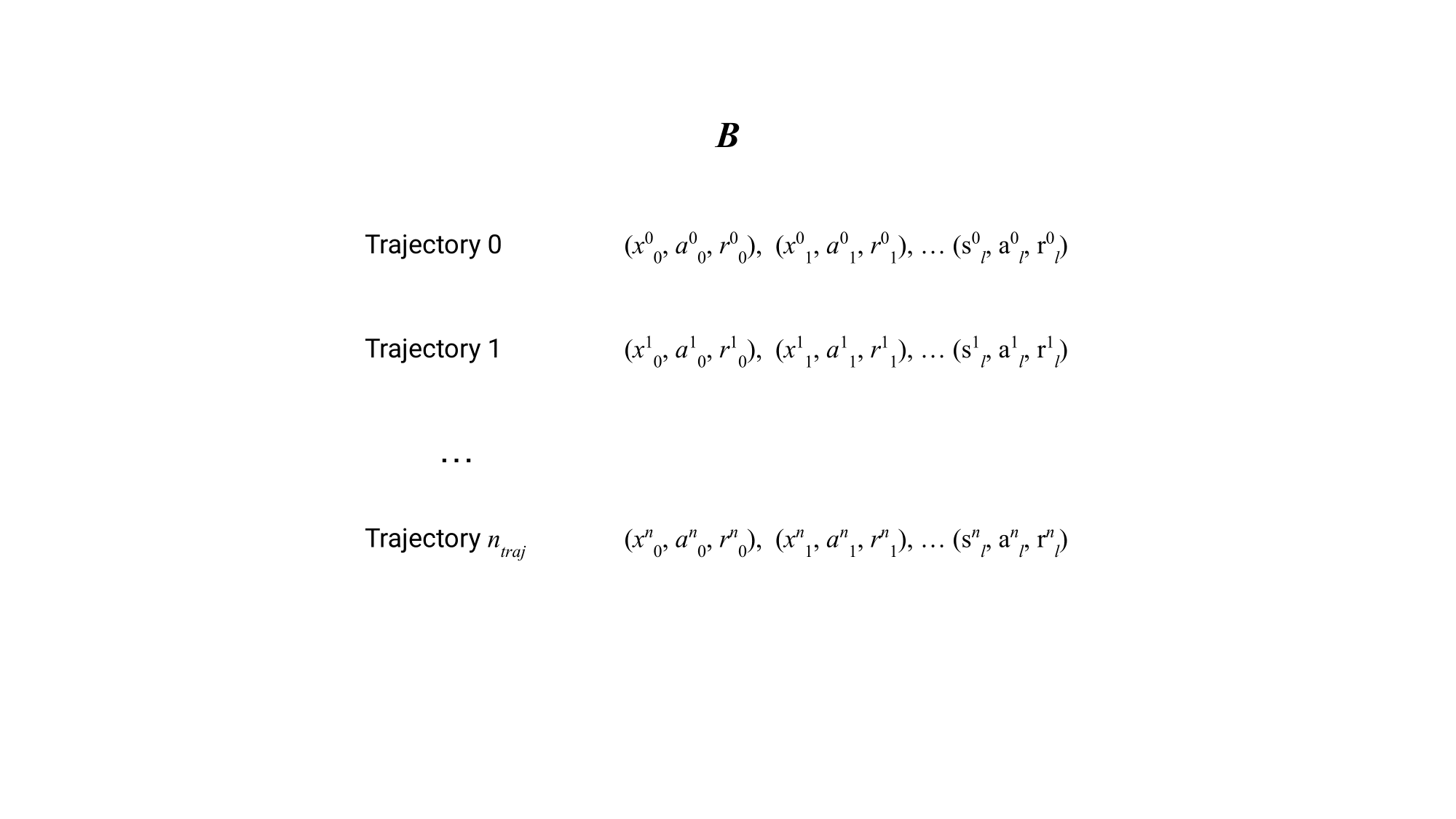

Next, we need something for the agent to retrieve from. The paper describes , a dataset of -step trajectories, where is at least 1. Each trajectory consists of input, action, and reward tuples, similar to the makeup of an experience buffer. I’ll be calling these tuples transitions throughout the post, even though I’m abusing the terminology a little.

Oddly, the action and reward in each transition doesn’t seem to actually be used, at least from their description of the algorithm.

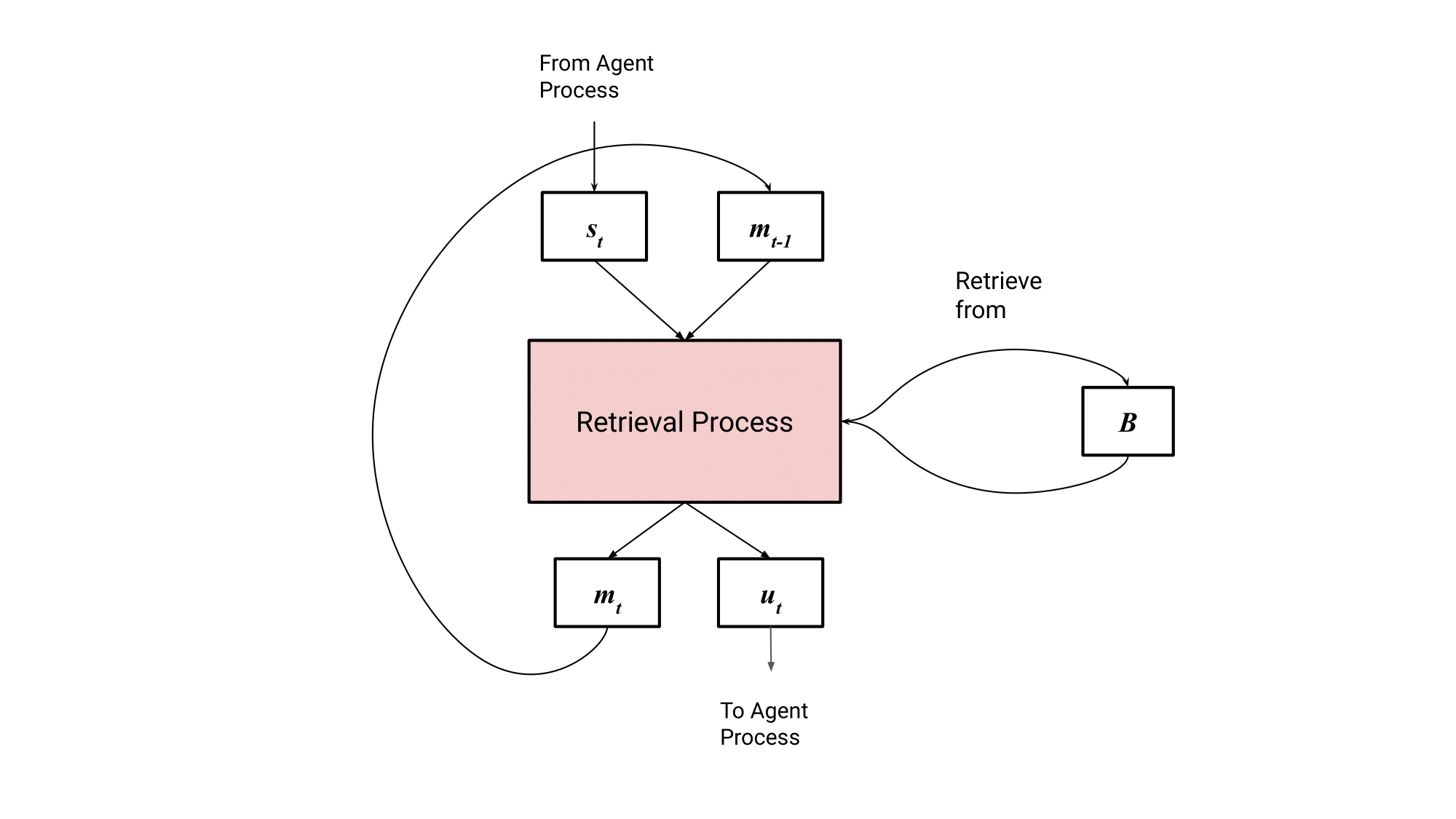

We need another process to actually perform retrieval. This process is a recurrent network that takes in the current (internal) state , does a round of retrieval, and outputs a summary of the items it retrieved in the form of . is sent to the agent process, causing its actions to be conditioned on both the state and retrieved items. The network also updates its hidden state , allowing information from previous rounds of retrieval to impact future retrievals. This whole process forms the retrieval process.

Let’s dive deeper into the retrieval process.

We’ll start by assuming the agent process has already encoded some input as and passed it to the retrieval process. Retrieval starts by uniformly sampling trajectories from our dataset, forming a sample batch. As previously discussed, each trajectory consists of tuples of the form (i.e. (input, action, reward)).

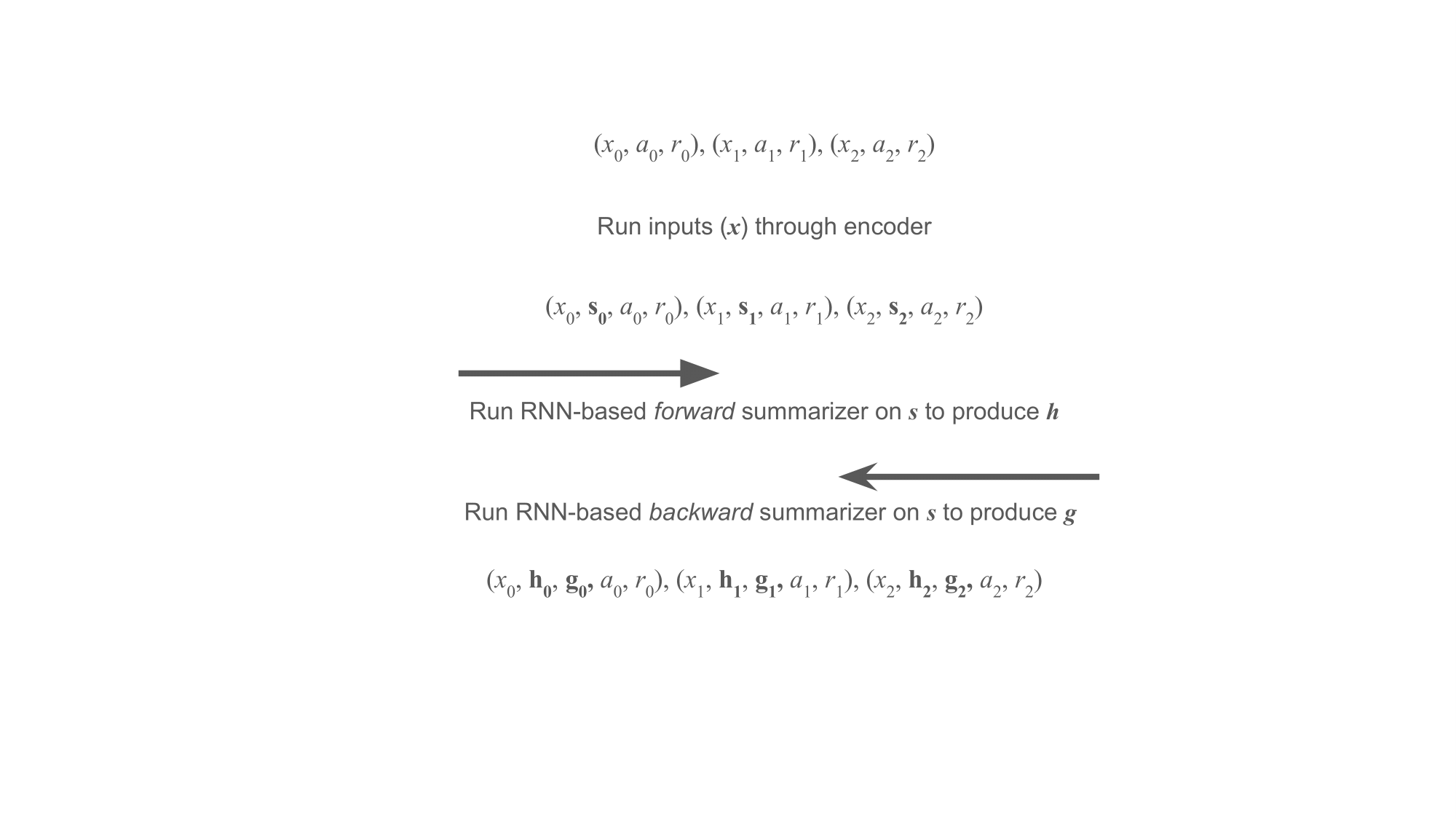

Before we actually retrieve from this batch, the trajectories are augmented with additional information through the use of summary functions. These functions, implemented as RNNs, take in a sequence of encoded inputs, thus we first apply our encoder on all transition inputs to produce . For timestep in the trajectory, the forward summarizer produces from . The backward summarizer produces from , going in the opposite direction. Once these summarizers are run on each transition, they are of the form .

At this point, we can actually perform retrieval!

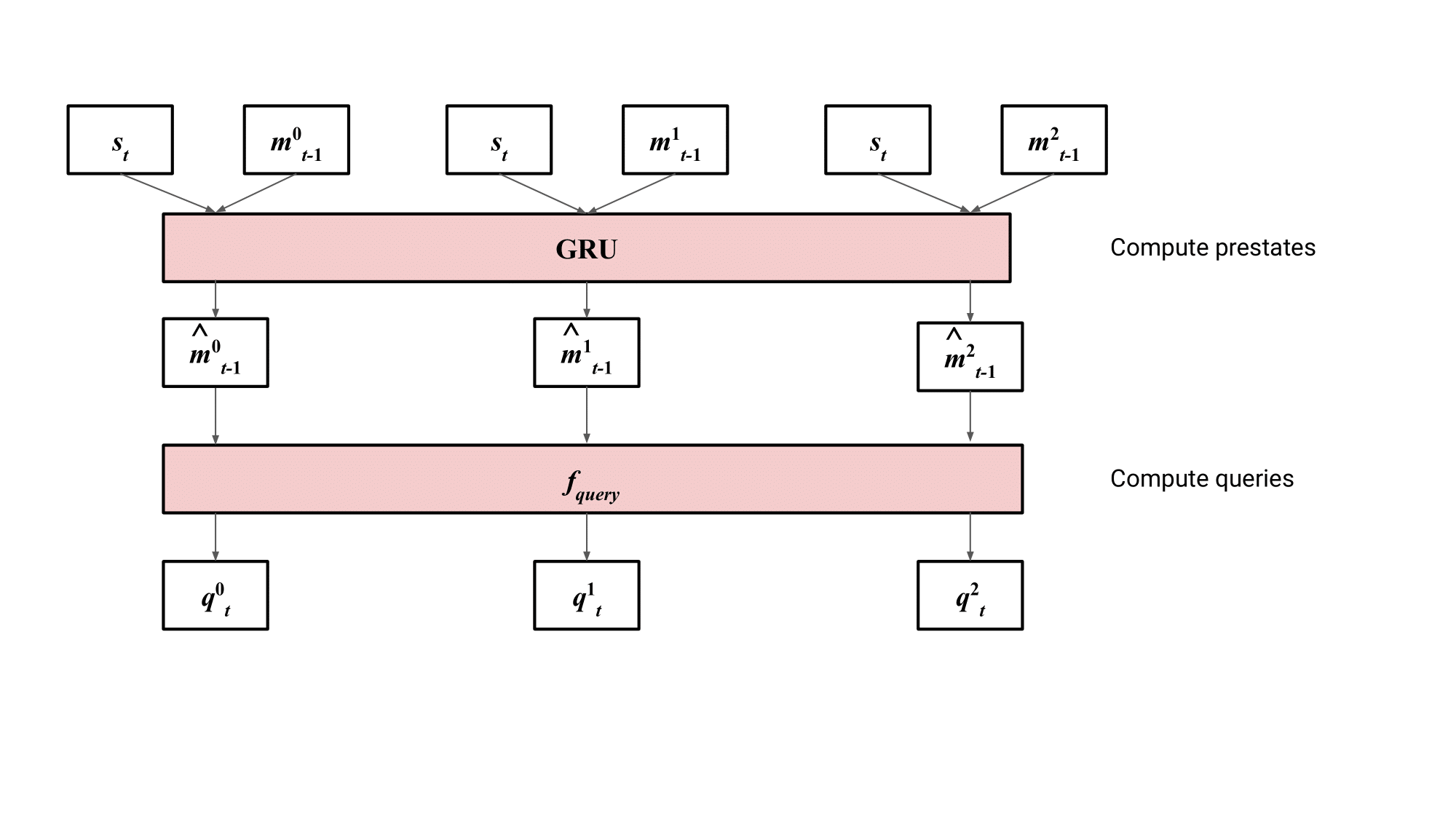

Previously, we mentioned that our recurrent retrieval model updates an internal state on each timestep. is not a single vector, but rather a series of vectors we call memory slots.

For each slot , we use a GRU to generate a prestate , using the previous retrieval state and the current agent state as inputs. These prestates are used to compute a query for each slot by simply running them through another network to produce .

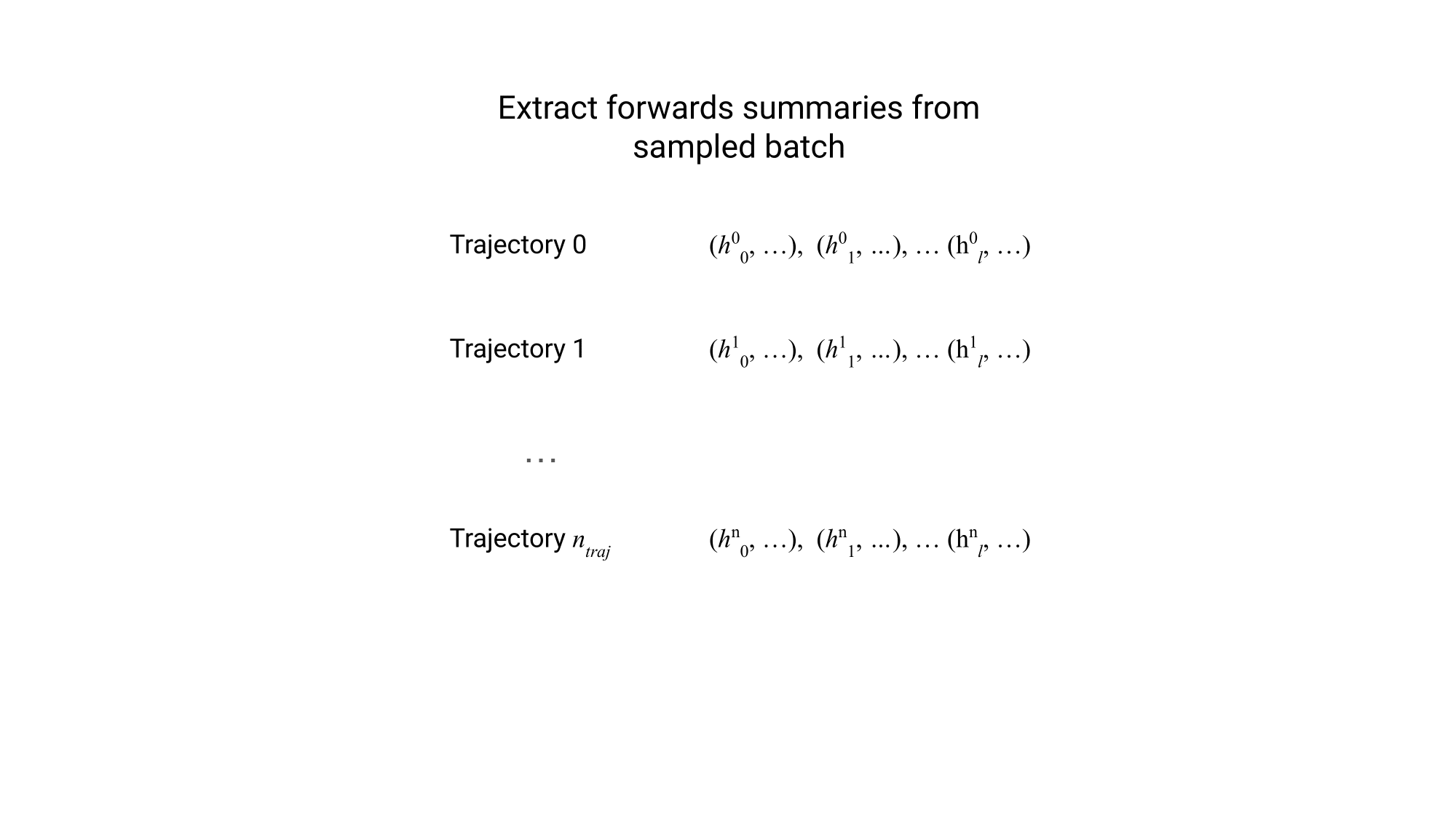

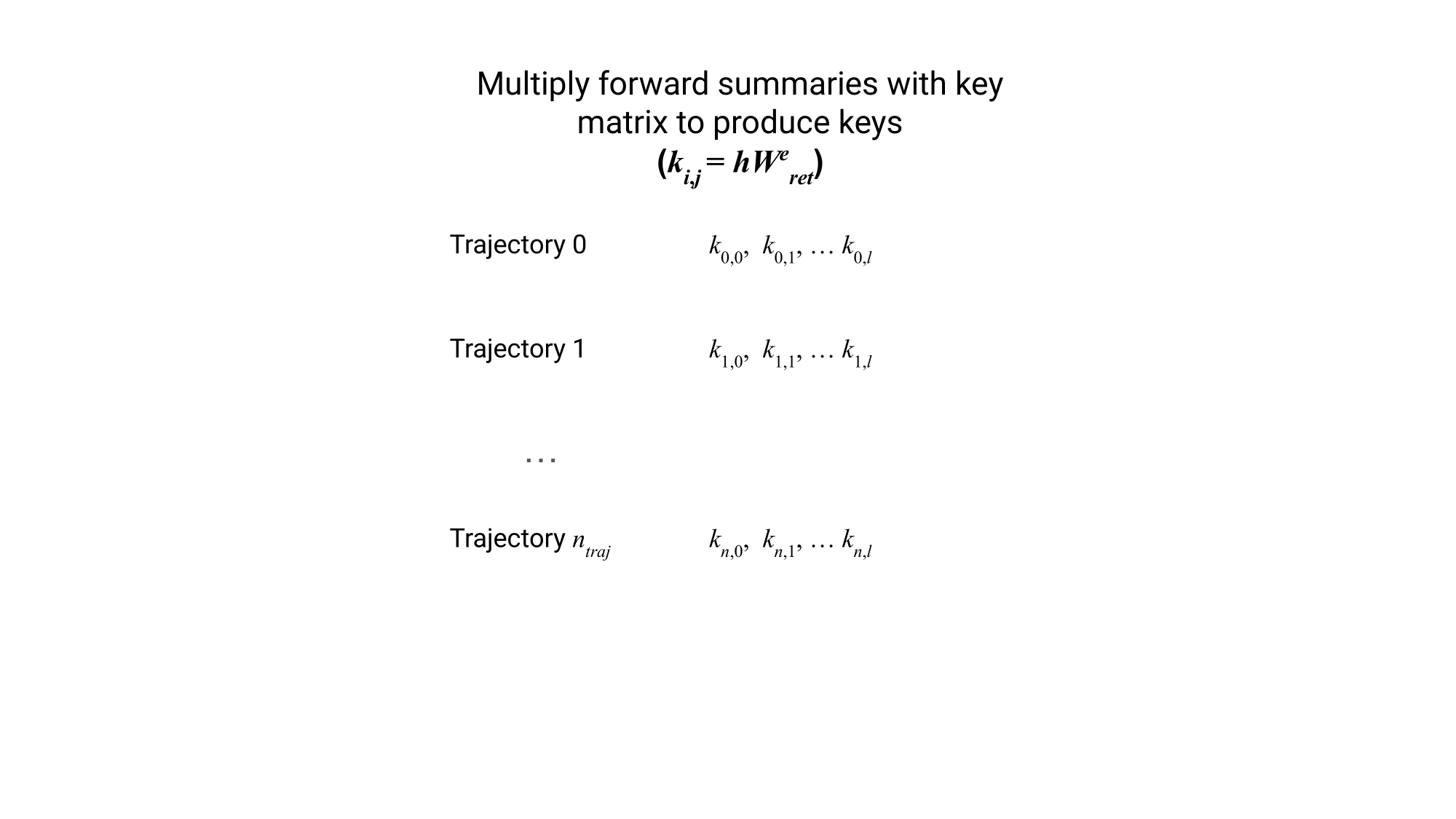

We compute keys by linearly projecting each forward summary , forming keys , where is the trajectory and is the timestep within the trajectory.

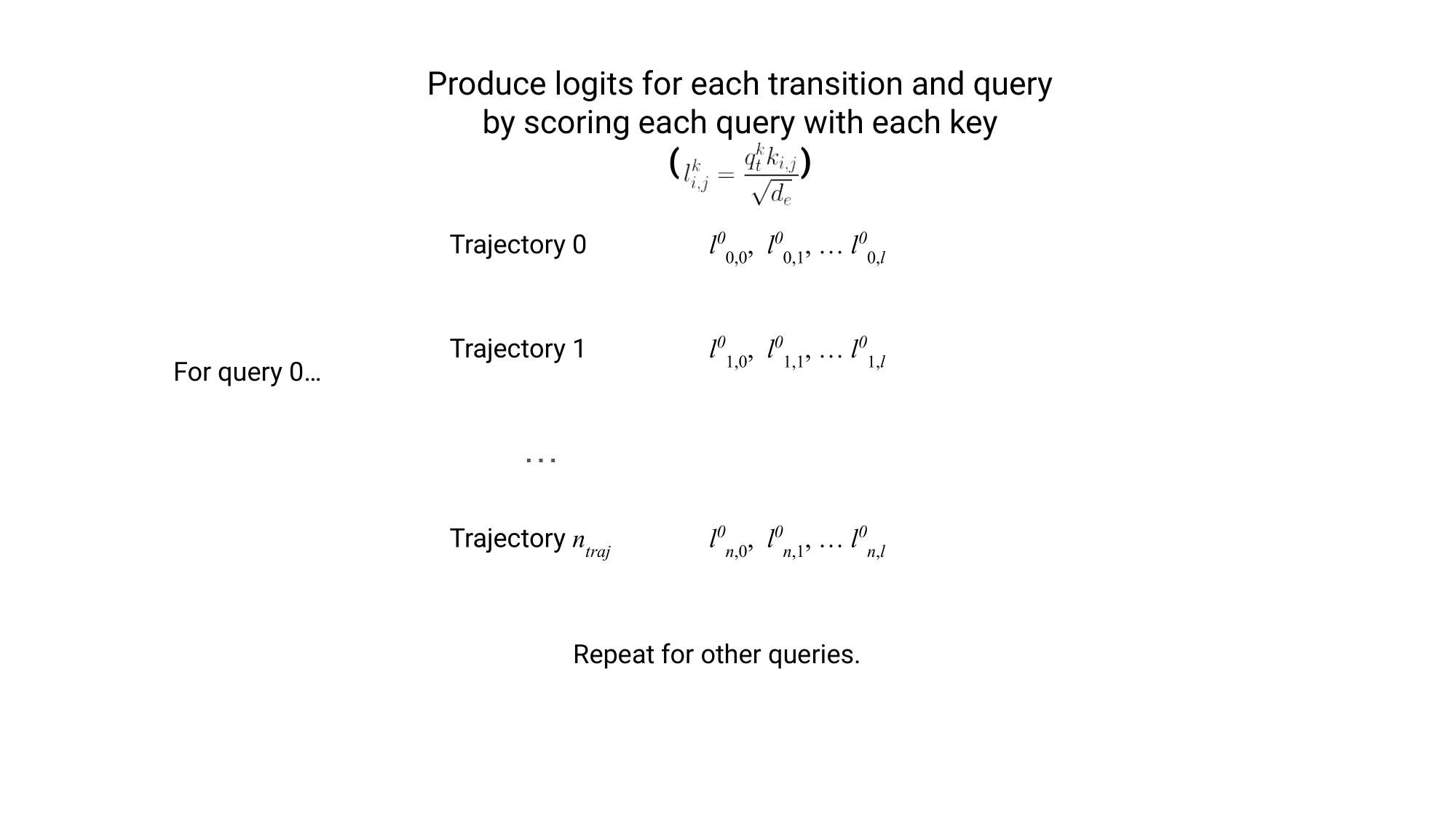

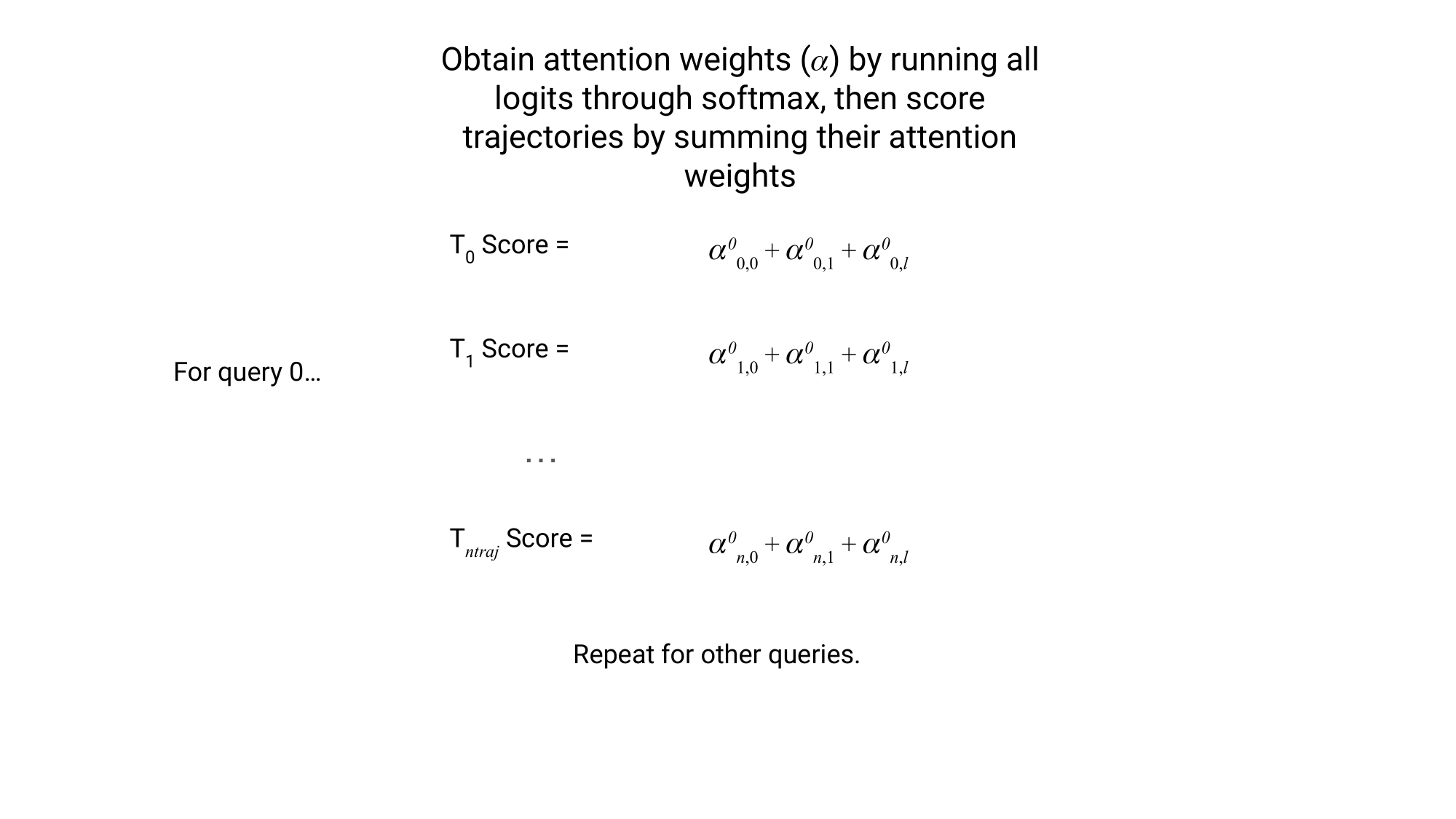

Each transition is scored by applying the scaled dot product between each key and query to produce a logit, then using softmax on the logits to compute attention weights. For those unfamiliar, is just the dimensionality of .

Each trajectory can now be scored by summing the scores of each of its constituent transitions.

We select the top-k highest trajectories for each memory slot. The transition scores are renormalized to account for the smaller set, i.e. the softmax is reapplied to the logits of our top-k trajectories’ transitions. Then, we compute the value of the slot by multiplying the backward summary () of each transition with a weight matrix (similar to the keys), multiplying that with the renormalized scores, then summing up these vectors, producing for each memory slot. All in all, this is just cross attention, with the queries as queries, the forward summaries as keys, and the backward summaries as values.

At this point, we have a set of values that we’ve retrieved, one for each memory slot.

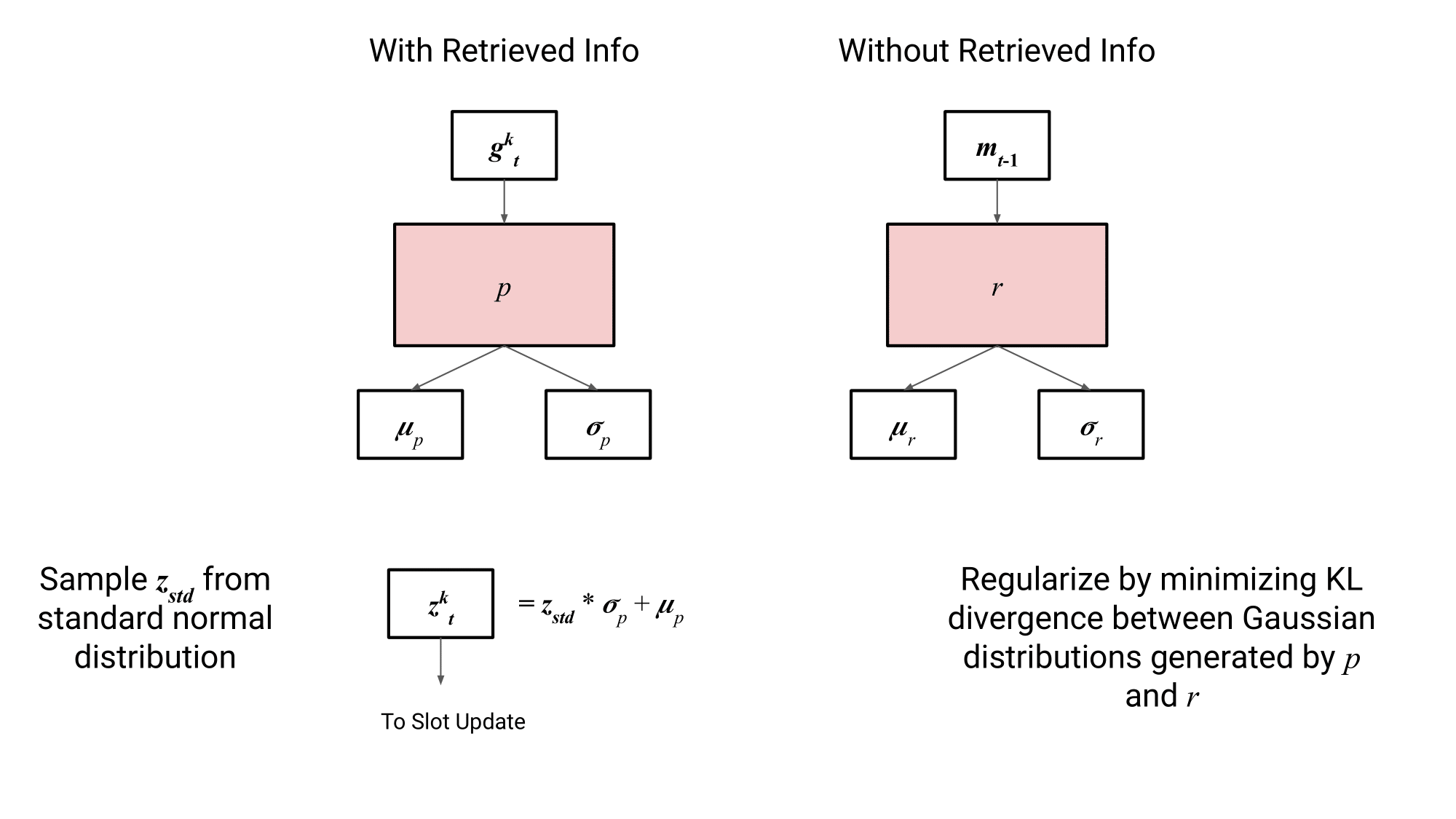

The authors parameterize two gaussian distributions — , which is conditioned on the memory slot’s retrieved information, and , which is only conditioned on the previous state of the memory slot.

It looks like they essentially use the same trick as variational autoencoders, where for a given input, a dimensional vector of means and standard deviations are generated, which are then used to sample values. , sampled from , is what we’re gonna use to update our slots, but we don’t want it to contain too much information. To accomplish this, the authors perform regularization by minimizing the KL divergence between the distributions generated by and .

is then used to update the slots’ representations by adding it to the prestates, . To get the final new representation of each slot, self attention is performed between slots, allowing them to share information.

Finally, we need to update our state with retrieved information . A cross attention operation is performed between the state and . is used to compute the query, while is used to compute the keys and values (i.e. via linear projection). The resulting value, , is added to , which is then passed to the agent so it can act upon it.

Conclusion

The big strength of the approach outlined here is that compared to a lot of episodic RL approaches, you’re being less prescriptive about the relevance criteria and how retrieved information is used. Instead of scoring past trajectories by state similarity, the networks themselves learn to retrieve and act upon the retrieved information.

In terms of the paper itself, I also found the experiments and ablations the authors performed to be thorough. They tested RARL on three tasks — Atari, Gridroboman, and BabyAI.

On Atari, they showed that RARL agents show performance gains over a standard R2D2 setup. Some of these performance gains were particularly big, such as on Frostbite, where they saw a ~200% improvement.

On Gridroboman (a multi-task, fully observable gridworld environment where an agent must complete various tasks involving picking up and putting down boxes), they showed that RARL agents can be trained on multiple tasks and are able to disambiguate tasks based on the retrieval dataset provided.

Finally, on BabyAI (a partially observable multi-task gridworld), they showed that even when trajectories from all tasks are provided in the retrieval dataset, RARL agents still improve over baseline R2D2 agents. This is in part chalked up to RARL being able to retrieve data from atomic tasks in order to solve more compositional tasks.

While I think this is an important paper for people studying the intersection of information retrieval and reinforcement learning, I do think there are a couple of issues, some personal.

First, I would have preferred not R2D2 at all. I feel like memory-based agents overlap with retrieval-based agents in function, and using something like a DQN would have made the results more clear, particularly for Atari. I do appreciate that Gridroboman used just a DQN for this reason.

Similarly, I’m not a big fan of how the retrieval process is an RNN whose state is dependent on prior retrievals. It makes the proposed approach less clean; I would have preferred a more straightforward mapping of current states to previous trajectories.

Finally, while the approach outlined here does improve over baseline DQN and R2D2 agents, this is more akin to attention over past trajectories rather than true retrieval. To make the problem tractable, the authors uniformly sample from the full retrieval dataset, but I suspect this leads to poor recall and final performance if the ratio of relevant trajectories to irrelevant trajectories is very small. This kind of relevance ratio is standard for most retrieval problems — for example, the dev set of MS MARCO designates one passage out of 8.8 million as relevant.

Additionally, rather than ranking individual trajectories, this approach operates on an entire batch of retrieved information (you have different slots, and each slot queries its own top-k set of trajectories, allowing the network to integerate data from number of trajectories). Ideally, the approach should work even when using 1 slot and greedily selecting the best piece of information.